Traveling to History: Twenty One

NORFOLK WAS ONCE A MAJOR STOP ON THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD: WHAT TRACES REMAIN TODAY?

By James F. Lee

Fugitive Slaves in the Dismal Swamp,” oil painting by David Edward Cronin, 1888. Collection: New-York Historical Society. {{PD US}}

For three months in 1855, 38-year-old Daniel Carr hid in the Great Dismal Swamp in southeastern Virginia “surrounded by wild animals and reptiles.”

Carr had escaped from bondage in North Carolina and was on a desperate journey northward seeking freedom.

But Carr’s immediate goal was Norfolk, Virginia.

The swamp offered refuge, but the city offered a means to escape.

Antebellum Norfolk was a teeming place with ships lining dozens of wharfs along the Elizabeth River. Once in Norfolk, escaped slaves would seek help from the extensive network of resistors to slavery, often ship’s crews of free and enslaved Blacks, who carefully hid those trying to escape in north-bound vessels.

When Carr reached Norfolk, he found one of those ships, the schooner City of Richmond captained by Alfred Fountain, a white man known for his sympathy to runaway slaves. Carr secured passage and was hidden aboard with 20 other freedom seekers.

Physical traces from that time are few, Norfolk having undergone catastrophic urban renewal during the 1950s and 60s, but some remain. The City of Norfolk has produced an excellent illustrated brochure “Waterways to Freedom,” highlighting remaining sites, locating those long gone, and telling the stories of freedom seekers and their helpers. But still, visitors trying to explore early Norfolk must use their imagination and look closely.

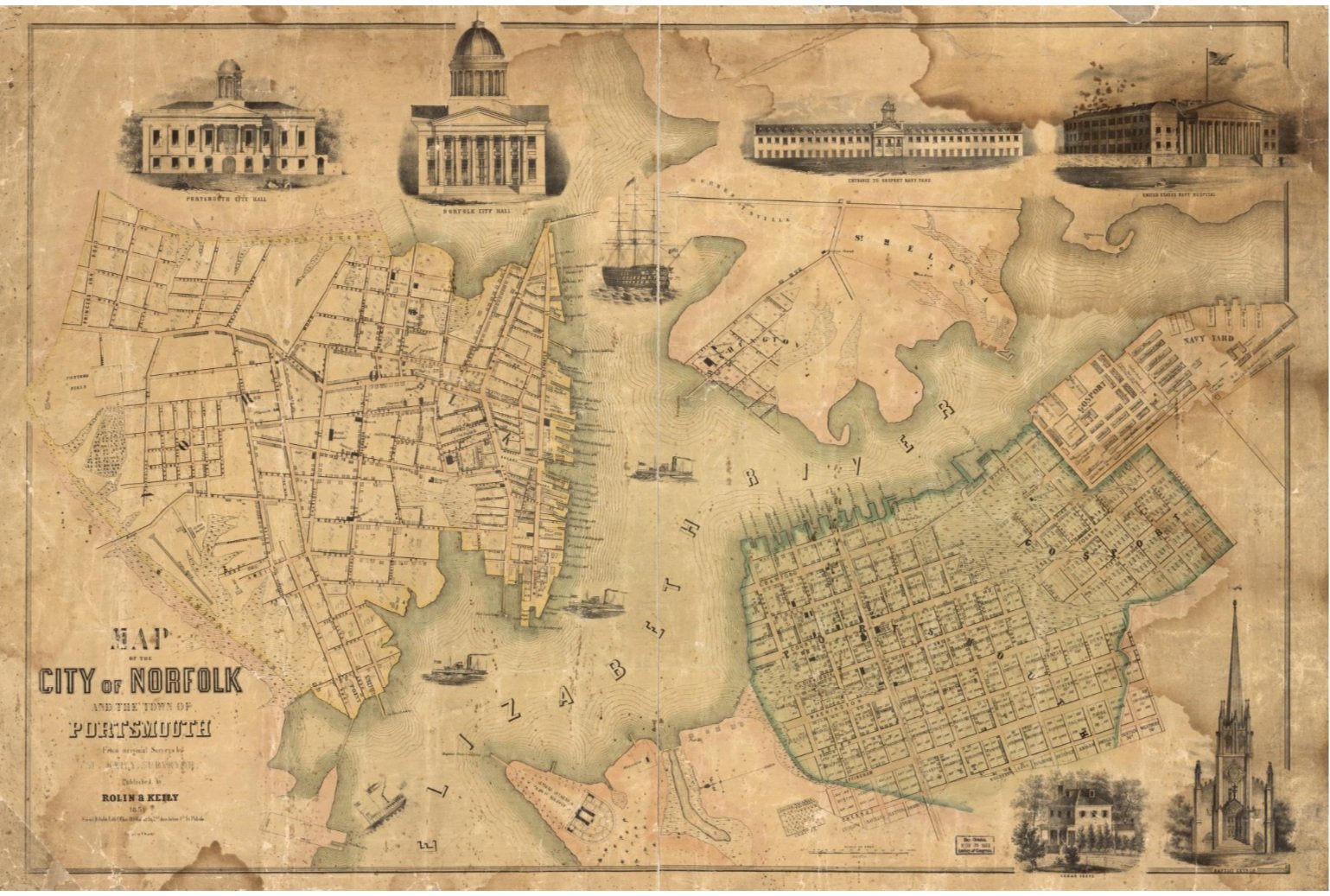

An 1851 map of Norfolk and Portsmouth by Robin and Keily. Norfolk is on the left side of the map. (Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division). {{PD US}}

For example, the City of Richmond was tied to the dock near today’s Otter Berth located to the west of Waterside Marina near Towne Point Park. You can see an indentation on the shoreline that now provides a couple of berths for tour boats and sailing ships.

A view of Waterside in Norfolk taken from the Portsmouth Ferry. This was the heart of the Norfolk waterfront in the 1850s. (Photo by James F. Lee)

Once hidden on the schooner, danger still lurked for Carr and his fellow refugees. Before the City of Richmond departed, an armed gang led by Mayor William Lamb boarded the vessel looking for suspected runaways. Lamb’s men swung axes on bulkheads and lockers, while others thrust spears into the wheat cargo in their search for the suspected hidden slaves.

In a desperate gamble, Captain Fountain grabbed an ax, asked the mayor where he would like him to strike, and smashed the ax down at that spot. This convinced the posse that no freedom seekers were aboard, and the schooner departed in peace, delivering 21 escapees to freedom in Philadelphia.

Mayor William Lamb, by the way, was the father of Confederate Colonel William Lamb, “the hero of Fort Fisher,” who followed his father’s footsteps himself becoming mayor. Their family home, the lovely Kenmure on West Bute Street, still stands. It is a private residence today.

“The Mayor and Police of Norfolk Searching Capt. Fountain’s Schooner.” Wood engraving likely by Edmund B. Bensell, 1872 (1879 edition). Freedom seeker Daniel Carr was aboard the City of Richmond during this incident. (University of Virginia Special Collections)

Many of the streets near the old wharves are gone, but one still existing from that time is Martin’s Lane, which today runs between East Main Street and Waterside Drive. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps from 1887 show that Martin’s Lane once extended northward from East Main to East Plume Street.

The wharves shown here on the Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River include the remains of Wright’s (left) and Higgins’ Wharfs, essential to Norfolk’s Underground Railroad history. (File Photo / The Virginian-Pilot)

Near the intersection of East Main and Martin’s Lane, in the vicinity of today’s Marriott Conference Center and Selden Market, Charles Martin once operated a dentist office with his enslaved apprentice, Sam Nixon. Nixon became skilled in dentistry and was a familiar sight throughout the city often making dental visits on his own, but he also had a secret life: he was a conductor on the Underground Railroad. Nixon eventually escaped to New Bedford, Massachusetts, changed his name to Dr. Thomas Bayne, and set up a dental practice. He returned to Norfolk after the Civil War.

Some buildings from that time still standing include the Old City Hall, several houses in the Freemason District, and the Old Academy Building, to name a few, but the locations of slave pens, auction houses, and Underground Railroad safe houses have been obliterated. This makes the remaining wharves so important.

Kenmure on West Bute Street, Norfolk. This was the home of Mayor William Lamb, leader of the posse searching Alfred Fountain’s schooner where 21 freedom seekers were hidden. (Photo by James F. Lee)

On the East Branch of the Elizabeth River beyond the Berkley Bridge where Harbor Park is today, vestiges of three forlorn wharves remain, including Wright’s Wharf and Higgins Wharf. These wharves were once essential to the Underground Railroad. Because of their out-of-the-way location from the central waterfront, it was safer to board escapees there to avoid the scrutiny of the slave-catching armed gangs searching ships and wharves for runaways. The steamship Augusta, for example, departed regularly from Wright’s Wharf, the most westerly of the three wharves, often carrying fugitive enslaved people.

A modern map of Norfolk showing Underground Railroad sites. Numbers 1 and 2 are Higgins’ Wharf and Wright’s Wharf respectively. Number 6 is Dr. Martin’s dental office, from which Sam Nixon, a conductor on the Underground, escaped. Number 9 is the approximate location of the City of Richmond’s dock. (VisitNorfolk)

The Great Dismal Swamp to the southwest of Norfolk played a significant role in Norfolk’s Underground Railroad history. Hundreds of runaway slaves from North Carolina and Virginia hid here, some permanently and some as a stop on their journeys. And that takes us back to the story of Daniel Carr.

Carr face the dilemma that so many enslaved people dreaded. He had lived with his wife and children in Portsmouth, but two years before his dramatic escape through Norfolk he was sold to an owner in North Carolina – separated from his family.

His only hope to ever be reunited with his family was to escape from his new owner and save money to purchase their freedom. But first he needed money to purchase his passage north – and this is where the economy of the Great Dismal Swamp came into play.

At that time, enslaved work crews were sent to the swamp to harvest cedar shakes from the abundant juniper trees to make shingles and barrel staves. It was one of the few successful commercial enterprises associated with the swamp. The enslaved workers labored with little oversight and were often paid by their owners if they achieved quotas. Sometimes the enslaved workers hired runaway slaves to bolster the number of shingles they produced.

The Underground Railroad Overlook at the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo by James F. Lee)

Permanent dwellers of the swamp were maroons, runaway slaves and their descendants living deep withing the interior. Freedom seekers such as Daniel Carr were temporary inhabitants, the swamp serving as a stop on their route to freedom.

Vestiges of the enslaved workers camps and maroon settlements are difficult to find today, but at the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge past inhabitants are memorialized at the Underground Railroad Overlook, near the Refuge headquarters, less than an hour’s drive from Norfolk.

The great Dismal Swamp today. This photo was taken on the shore of Lake Drummond in the interior of the swamp. (Photo by James F. Lee)

Set among the quiet of loblolly pines and sycamores, three panels describe the lives of those once inhabiting the swamp, highlighting the economy of timbering and commercial lumbering, and today’s emphasis on conservation and wildlife. Interesting photos show glass shards from maroon settlements, and a Native-American blade sharpening tool, likely used by maroons. There are also samples of cedar shakes.

After Daniel Carr’s ordeal in the Dismal Swamp and his dramatic escape from Norfolk, he eventually made his way to Canada. It is unknown if he ever reunited with his family.

A drawing of Osman, a maroon in the Great Dismal Swamp. Image by David Hunter Strother in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 1856. {{PD US}}

Sources:

The Underground Railroad Records. William Still, Ed. By Quincy T. Mills.

Virginia Waterways and the Underground Railroad. Cassandra Newby-Alexander.

Waterways to Freedom: Norfolk, Virginia’s Underground Railroad Network. VisitNorfolk.